From an industry-standards point of view, not every terminal is meant to be soldered. Many crimp lugs and ring terminals are tested and listed as crimp-only under standards such as UL 486A-486B for wire connectors. If you add solder to a crimp-only connector, you may change how it handles heat, vibration, and strain – and in some regulated applications, that can invalidate the rating.

On the other hand, there are terminals designed specifically for soldered terminations:

-

Solder cups on connectors

-

Tinned ring or spade terminals meant for soldering

-

PCB pins and tabs following IPC J-STD-001 workmanship criteria

So the first proper step in any solder wire splice is:

-

Read the datasheet. Check whether the terminal is rated for crimp, solder, or both.

-

Respect the listing. For mains and safety-critical wiring, follow UL/CSA and local code, and defer to a licensed electrician if you’re unsure.

-

Use solder for the joint, not as a glue. Whether you’re making a butt splice or soldering into a terminal, the conductor should be held mechanically before the solder ever hits it.

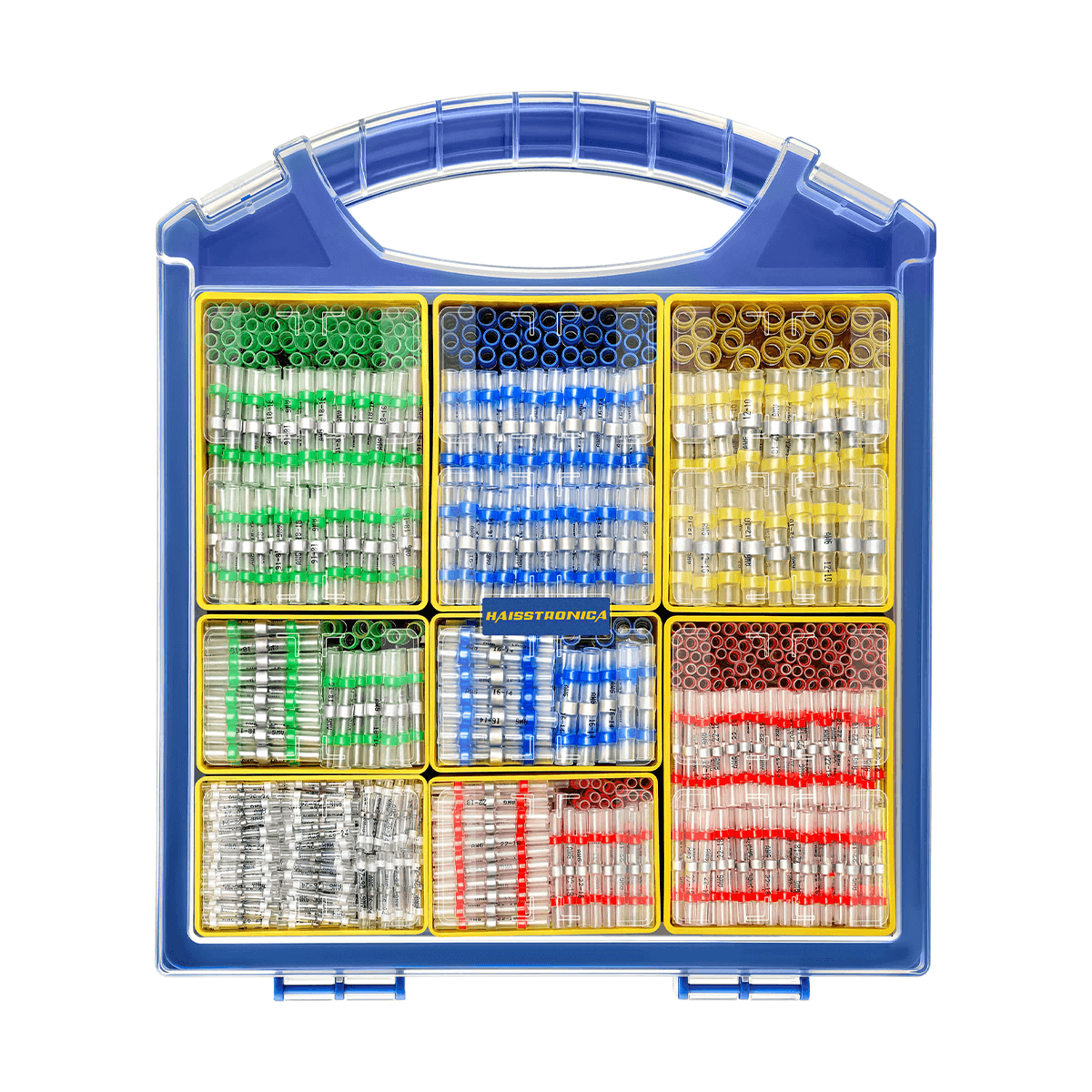

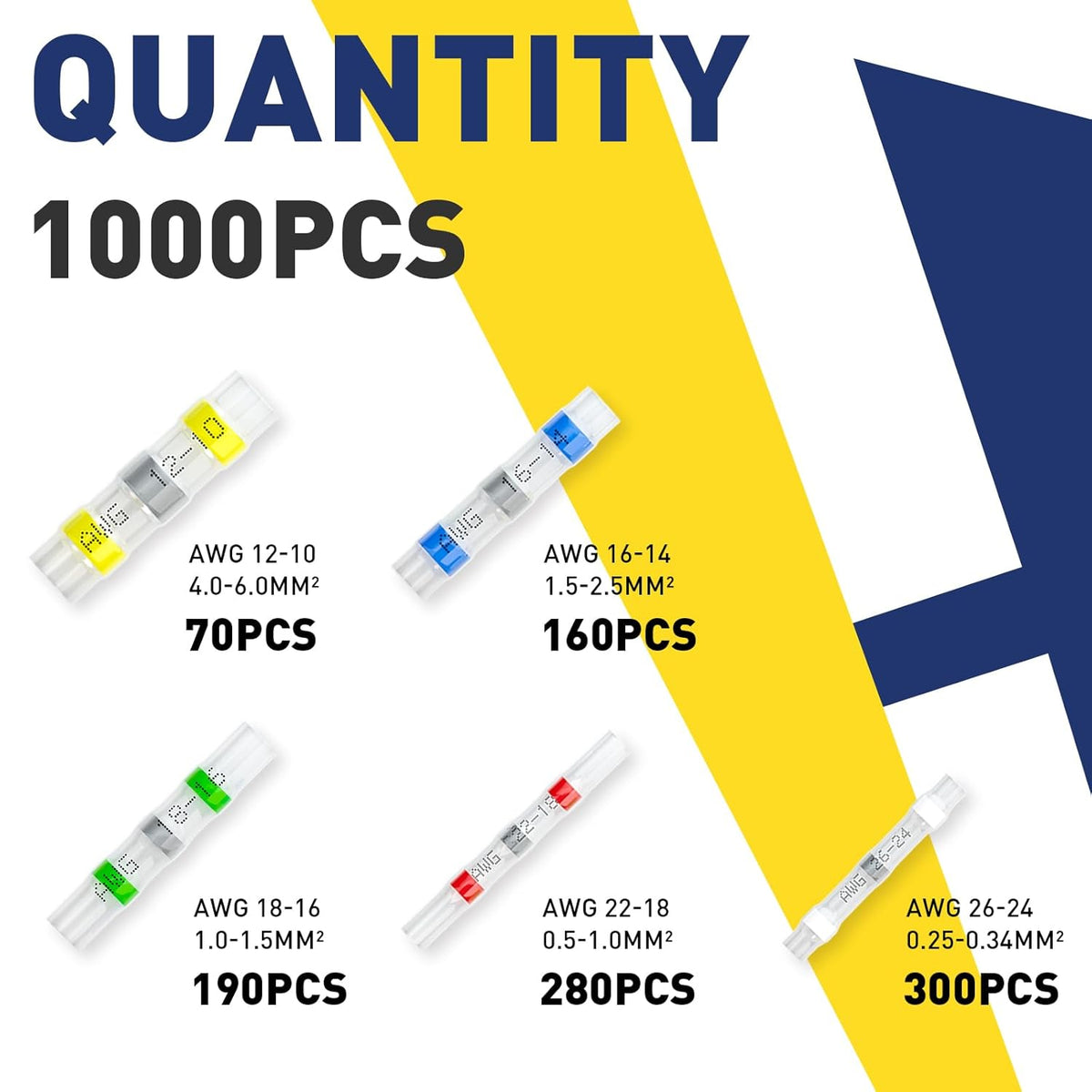

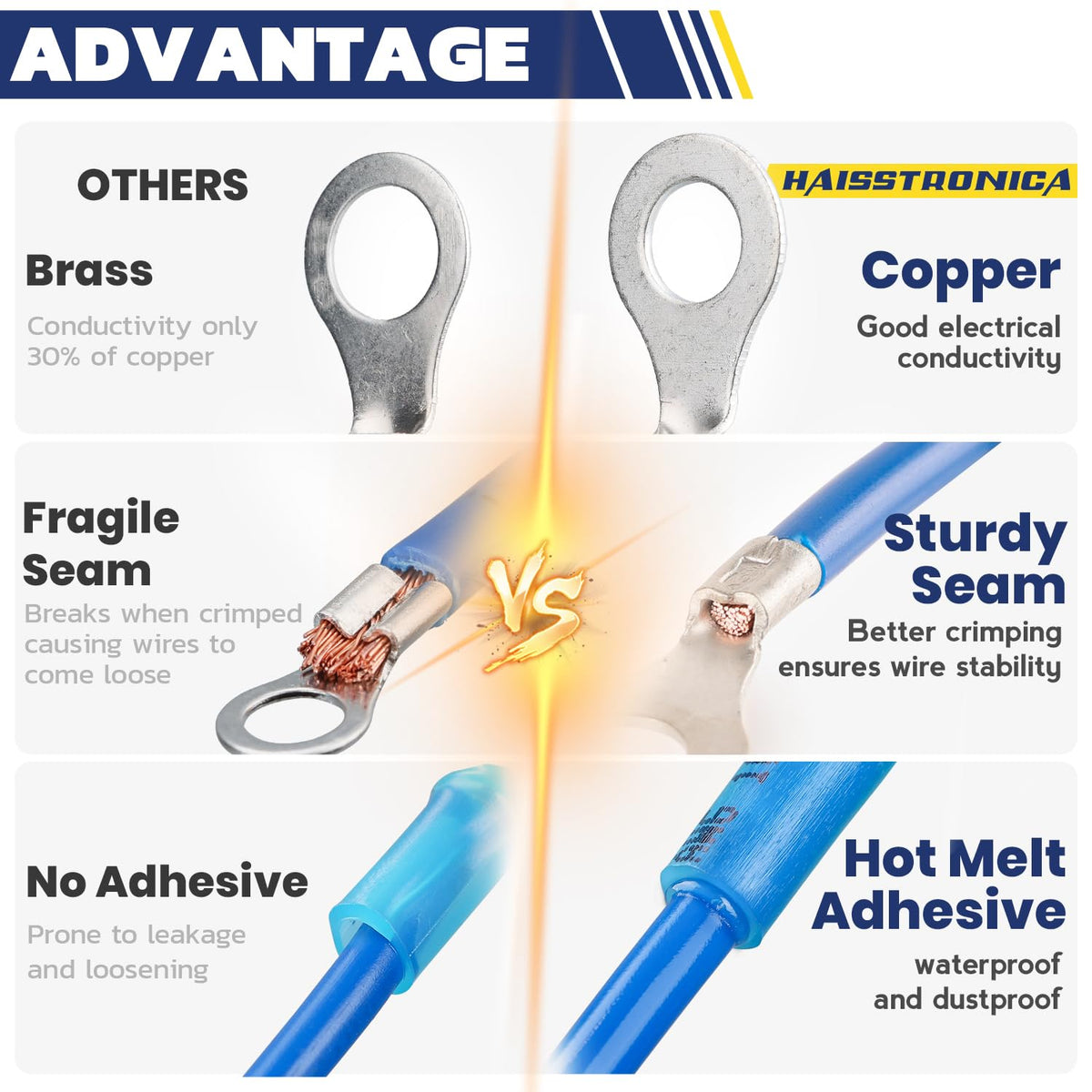

If you’re a DIYer or electrician working on low-voltage or automotive harnesses and you’d rather avoid the “can I solder this lug?” question, this is where pre-engineered options like a solder wire splice in a heat-shrink sleeve shine. haisstronica’s solder & seal butt connectors and terminals are designed so the alloy, flux, and heat-shrink work together, giving you a repeatable, code-friendly alternative to improvising on generic lugs.

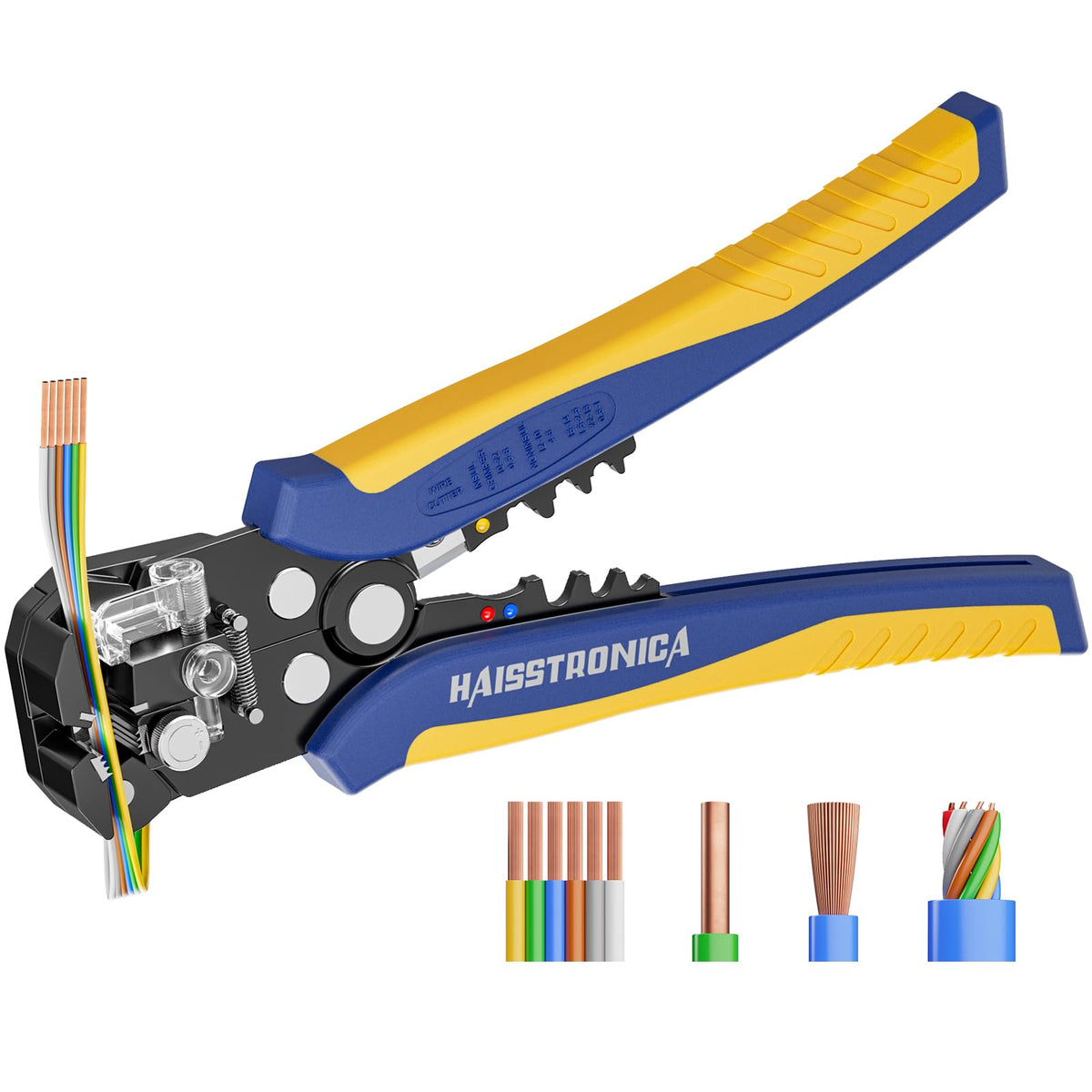

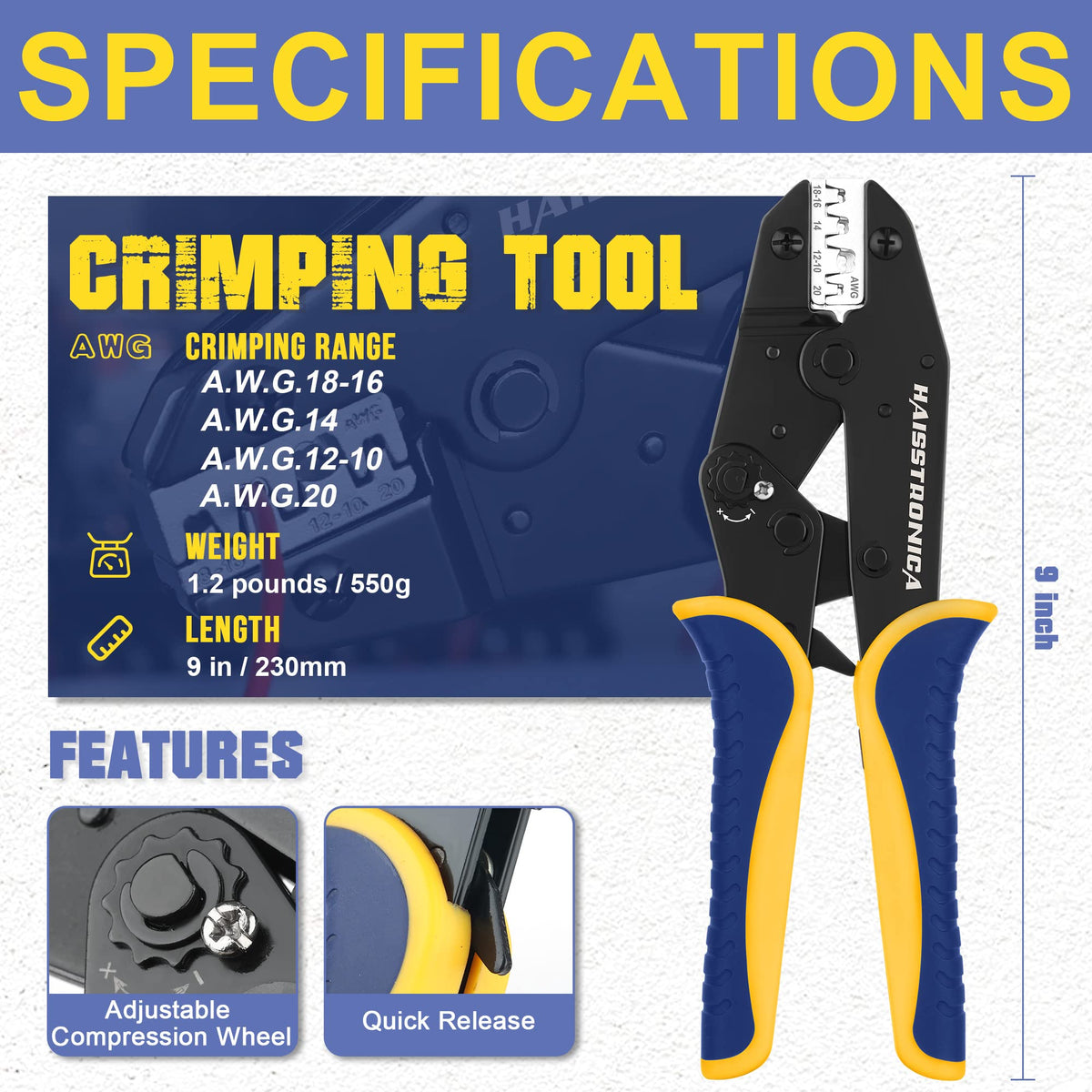

Tools and Materials for Soldering a Wire into a Terminal — solder wire splice toolkit

If you try to “wing it” with a random iron and mystery solder stick from the bottom drawer, you’ll fight every joint. A proper solder wire splice into a terminal starts with the right gear:

Core soldering tools

-

Temperature-controlled soldering iron

For most copper wire terminations you want a tip temperature in the ~315–370 °C (600–700 °F) range, depending on the solder alloy and terminal mass. A basic station with adjustable temp and interchangeable tips is a huge upgrade over a single-temperature pencil. -

Appropriate tip shape

A small chisel or screwdriver tip is usually better than a sharp conical “needle”. You want surface area for heat transfer, especially on ring or spade terminals. -

Quality solder wire (not mystery solder stick)

For typical electronics and control wiring, a lead-free tin-silver-copper or tin-copper solder with a rosin-based flux core is common. The solder melting point is usually in the 217–227 °C (423–441 °F) range for lead-free alloys, slightly lower for 63/37 SnPb.-

For heavier lugs, a slightly larger diameter solder wire or pre-formed solder sticks can help feed metal faster once the joint is fully heated.

-

-

Flux (if needed)

Even if your solder wire has flux, using additional no-clean or RMA flux on oxidized terminals can dramatically improve how your solder wire splice wets and flows.

Handling, support, and protection

-

Helping hands or a vise – Your joint should not be moving while the solder solidifies.

-

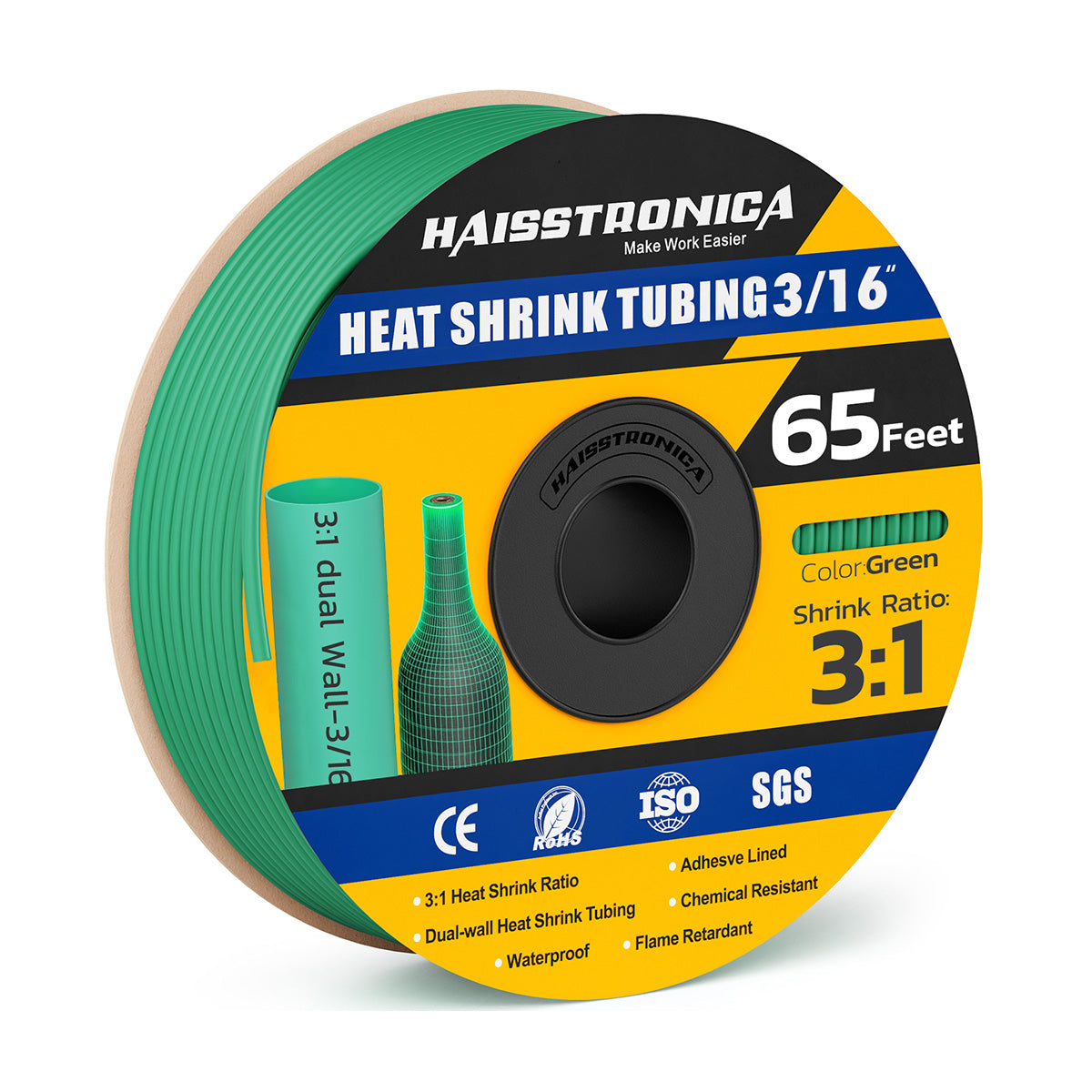

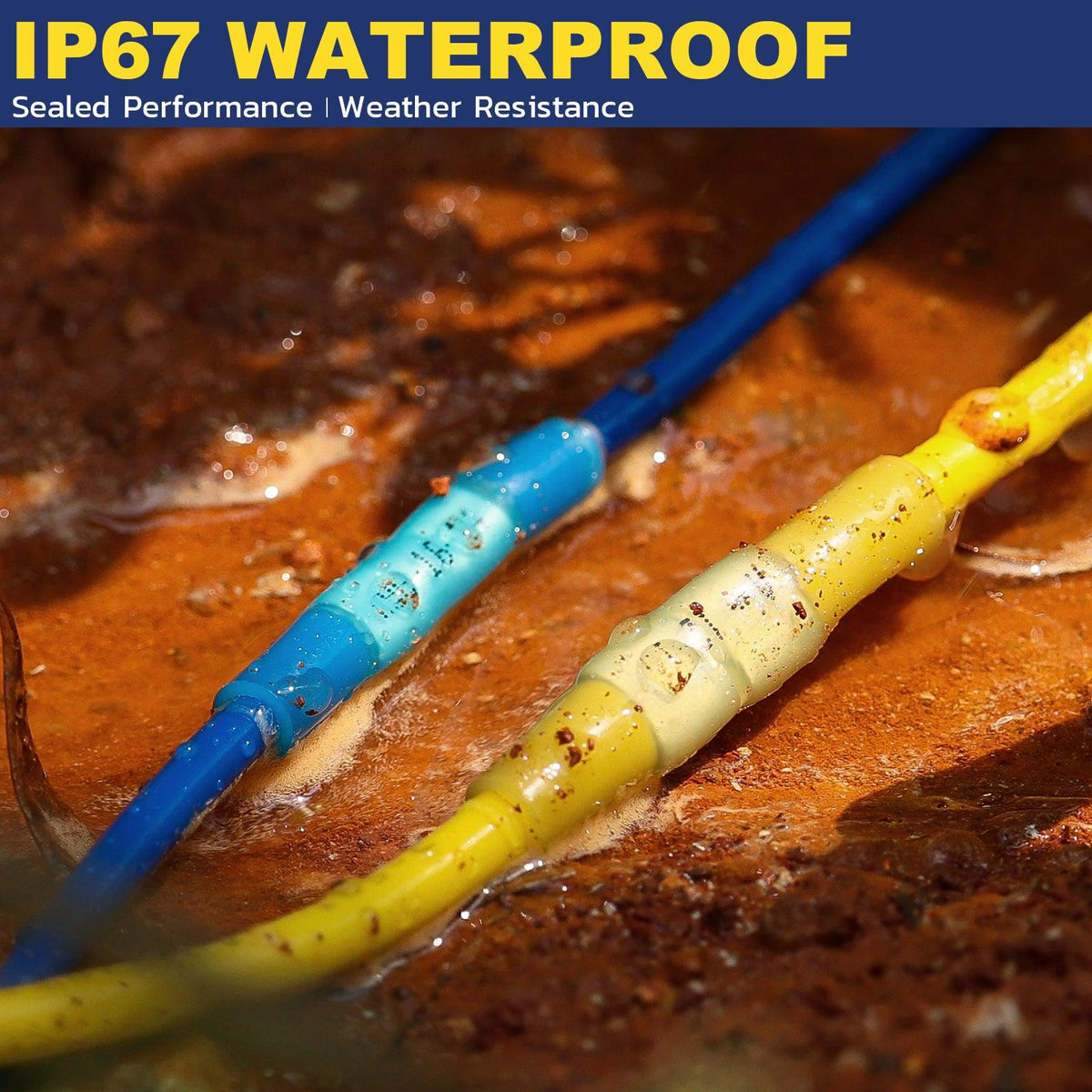

Heat-shrink tubing or heat-shrink solder sleeve – To insulate and provide strain relief after the joint cools.

-

Safety gear – Eye protection, fume extraction or at least a fan, and a heat-resistant work surface.

If you prefer something more integrated than loose heat-shrink, haisstronica’s solder sleeves and solder & seal butt connectors combine the solder ring, flux, and tubing in one part. That lets you get a proven solder wire splice and environmental seal without juggling separate solder, flux, and tubing on the bench.

Prep Work: Getting the Wire and Terminal Ready for Solder — solder wire splice prep

Most “bad joints” are doomed before the iron ever touches them. The clean-prep-support sequence is the same whether you’re soldering to a ring terminal, spade, solder cup, or making a straight solder wire splice between two conductors.

1. Strip the wire correctly

-

Length: Strip just enough insulation so that all bare strands will sit inside the terminal barrel or cup, with no copper exposed beyond the metal and no insulation trapped inside the solder area.

-

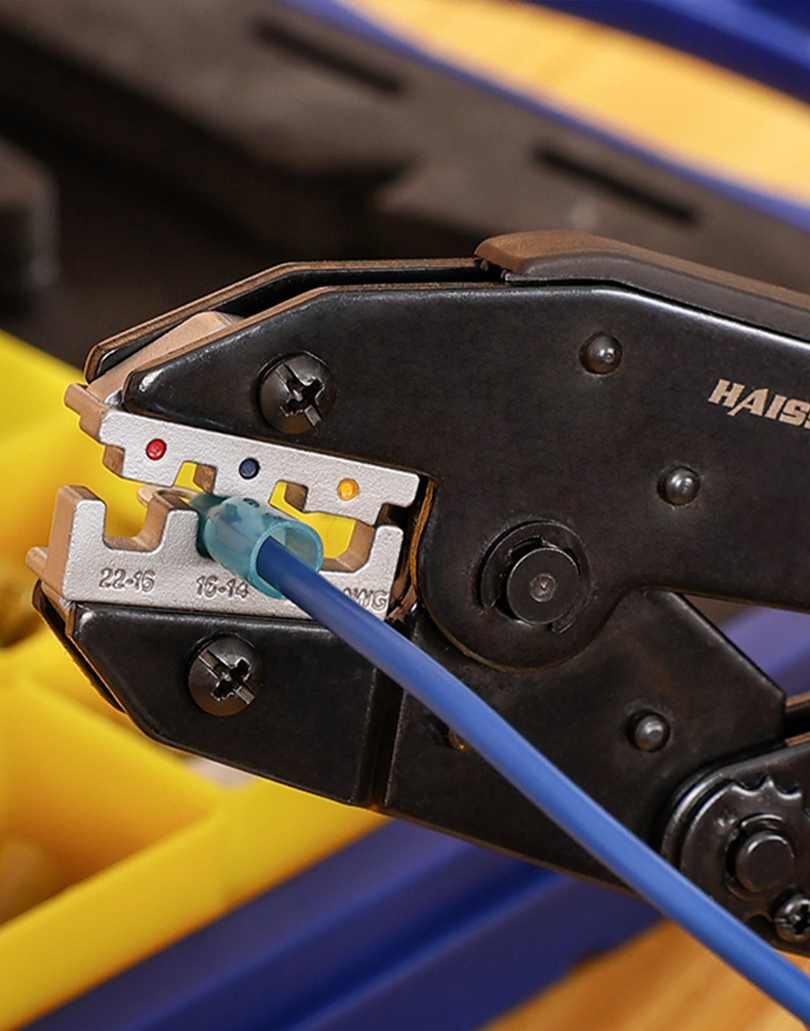

Method: Use a proper stripper sized to the gauge; don’t nick or cut strands. Nicked conductors are weak points that can break later, especially in vibration.

For marine and automotive work, tinned copper wire and tinned solder terminals help resist corrosion before you even start soldering.

2. Clean and tin if appropriate

-

Clean: If the wire or terminal looks dull, dark, or has visible oxidation, add a touch of flux and wipe with a lint-free cloth or brush.

-

Pre-tin (optional):

-

Lightly tin stranded wire if you’re going into a solder cup or PCB tab – but avoid building up a large, stiff blob.

-

For many wire-into-barrel terminations, it’s better to insert bare, fluxed strands and let the solder flow through the barrel from the heat side.

-

Remember: tinning is about wetting strands so they accept solder quickly; you don’t want to pre-form the entire solder wire splice outside the terminal.

3. Dry fit and support

Before you heat anything:

-

Insert the stripped wire into the terminal and confirm:

-

All strands fit comfortably inside.

-

The insulation butts right up against the back of the barrel or cup.

-

-

Clamp the wire and the terminal so they can’t move. Any motion while the solder transitions through its solder melting point will create a weak, grainy joint.

If you’ll be adding heat-shrink or a heat shrink solder sleeve, slide it over the wire now and park it away from the hot area so you don’t accidentally pre-shrink it.

When you’d rather skip manual prep for small harnesses or repairs, haisstronica’s pre-engineered solder wire splice connectors (solder & seal style) give you controlled strip length windows and built-in strain relief, so your “prep” is mostly just strip, insert, and heat.

How to Actually Solder the Wire into the Terminal — solder wire splice step-by-step

Now we’re finally ready to talk about the hands-on process. The core rule: heat the joint, not the solder. You want the terminal and conductor to bring the solder wire splice up to temperature, so the solder is drawn into the joint by capillary action.

1. Heat from the metal side

-

Place the iron tip so it contacts both the terminal barrel/cup and the conductor, as much metal as possible.

-

Give it a few seconds to soak. Heavier lugs can take longer; don’t rush and start feeding solder too early.

If you’re working with a ring or spade lug, the iron usually sits on the underside of the barrel, while you feed solder from the top.

2. Feed solder into the joint, not onto the tip

-

Touch the solder wire to the opposite side of the joint from the iron, not directly to the tip.

-

When the joint reaches the proper solder melting point, the solder will suddenly begin to flow around and into the strands.

-

Keep feeding until you see:

-

The barrel is filled but not overflowing.

-

The wire strands are fully wetted and you can’t see sharp individual strand outlines.

-

No giant glob or “icicle” forms outside the connection.

-

If the solder just balls up and falls off, the joint isn’t hot or clean enough. Stop, clean, re-flux, re-heat, and try again. For difficult terminations, a small bit of additional flux or using a slightly higher-mass iron tip helps the solder wire splice flow properly.

3. Stop heating and hold still

Once the joint is filled:

-

Remove the solder wire first.

-

Then lift the iron away while holding the wire and terminal completely still.

-

Keep it motionless for a few seconds until the surface goes from shiny liquid to a smooth, slightly dull solid.

Avoid blowing on the joint – forced cooling can create thermal shock and micro-cracks.

4. Inspect the joint

A good solder wire splice into a terminal should have:

-

Smooth, concave fillets between wire and barrel

-

No pits, cracks, voids, or dull/grainy “cold solder” look

-

No insulation pulled back from overheating

-

No solder wicking inches up the conductor to make it stiff and prone to breakage

For critical work, industry standards like IPC J-STD-001 and NASA-STD-8739.3 describe detailed visual criteria for acceptable soldered terminations – they’re worth a look if you want to raise your workmanship game.

Once the joint passes visual inspection and is fully cool, slide your heat-shrink – or better yet, a haisstronica heat shrink solder sleeve or solder & seal boot – over the area, then shrink it to add insulation and strain relief so your good joint stays good in the field.

Conclusion: When in Doubt, Let the Joint Decide

The “proper” way to solder a wire into a terminal isn’t really about hand tricks; it’s about respecting what the joint needs:

-

A terminal that’s meant to be soldered (or a purpose-built solder wire splice connector)

-

Clean, correctly stripped conductor fully supported inside the metal

-

Enough controlled heat to bring everything above the solder melting point

-

Flux and solder that wet the metal instead of just sitting on top

-

Zero movement until the joint solidifies – followed by decent strain relief

If you’re doing one-off repairs on the bench, a temperature-controlled iron, quality solderstick or wire solder, and a bit of practice will carry you a long way. If you’re building harnesses for marine, automotive, or outdoor use, you’ll often save time and failures by stepping up to higher-grade terminals, sealed electrical connectors, or integrated solder wire splice solutions like haisstronica’s solder & seal kits, which bundle solder, flux, and heat-shrink into one repeatable part.

Either way, the goal is the same: not just a shiny joint, but a connection that survives vibration, moisture, and time without making you open the panel again.